M Room Tech

at her desk at Wilton park.

Twenty-one year old Catherine Townshend had been working briefly in the Map Room at Trent Park when she was transferred to Wilton Park, to join a department called MI19(e). The section was responsible for the setting up the ‘M Rooms’ at different sites (whether in Britain or abroad), including the technical equipment, its accommodation and interviewing the secret listeners.

On October 5, 1942, her boss Major Back called her into his office and explained that he was being called away on undisclosed secret duties. She was the only person who knew the work and therefore was the new head of the section.

The head of one of the most sensitive and hush-hush roles within MI9 /MI19 was now a woman. It was a first for women working in intelligence. Catherine went on to send listening equipment and recording machines to interrogation centres elsewhere in England, the Middle East, India and Australia.

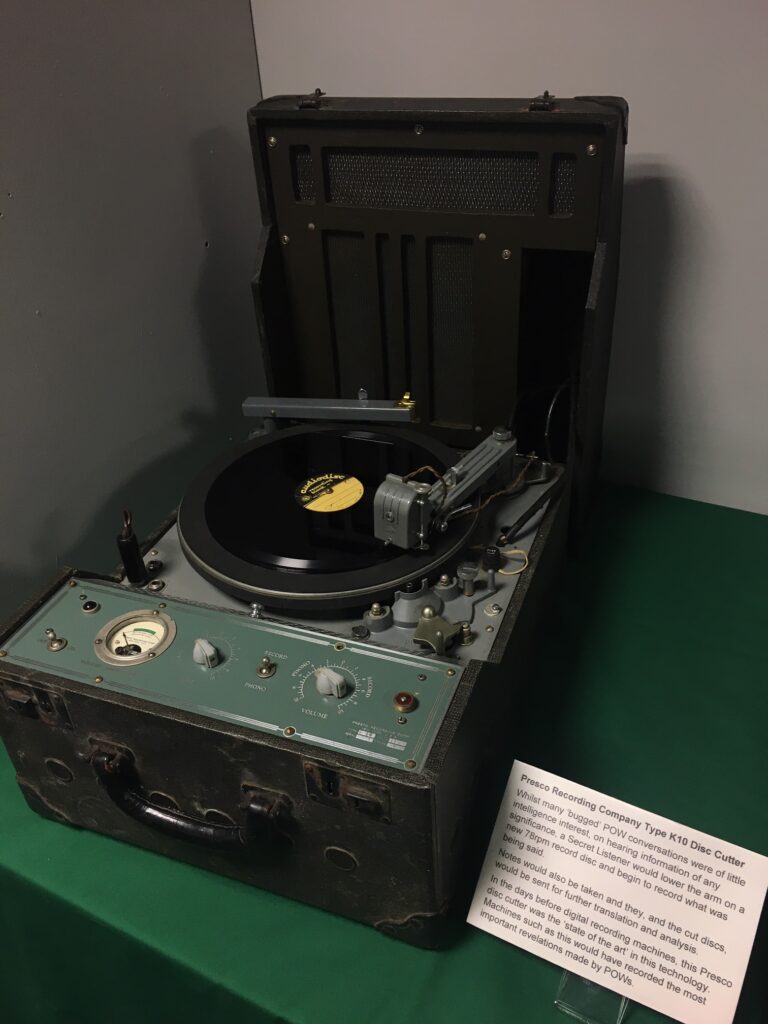

The microphones were the latest state of the art technology and supplied to the listening sites by the Radio Corporation of America (RCA). Trent Park was kitted out with fifteen “88A pressure” microphones and nine portable disc recorders. From 1942, Latimer House and Wilton Park had microphones installed under the direction of engineer F. Doust.

The machines could record conversations in any of the wired rooms of the prisoners.

As soon as the secret listeners heard something which of valuable, they pushed a switch to start a turntable revolving, and pulled a small leaver to lower the recording-head onto the record. They had to identify which prisoner was speaking by their voices and accents and kept a log, noting what the prisoners were talking about. In that log, they noted down the time of day and the subjects that were recorded, so that the next shift could see at a glance what had been happening.

When the acetate 78″ record had been cut, the secret listener went to a different room to transcribe what he had just recorded. Another secret listener else had to take over the monitoring of the cells.

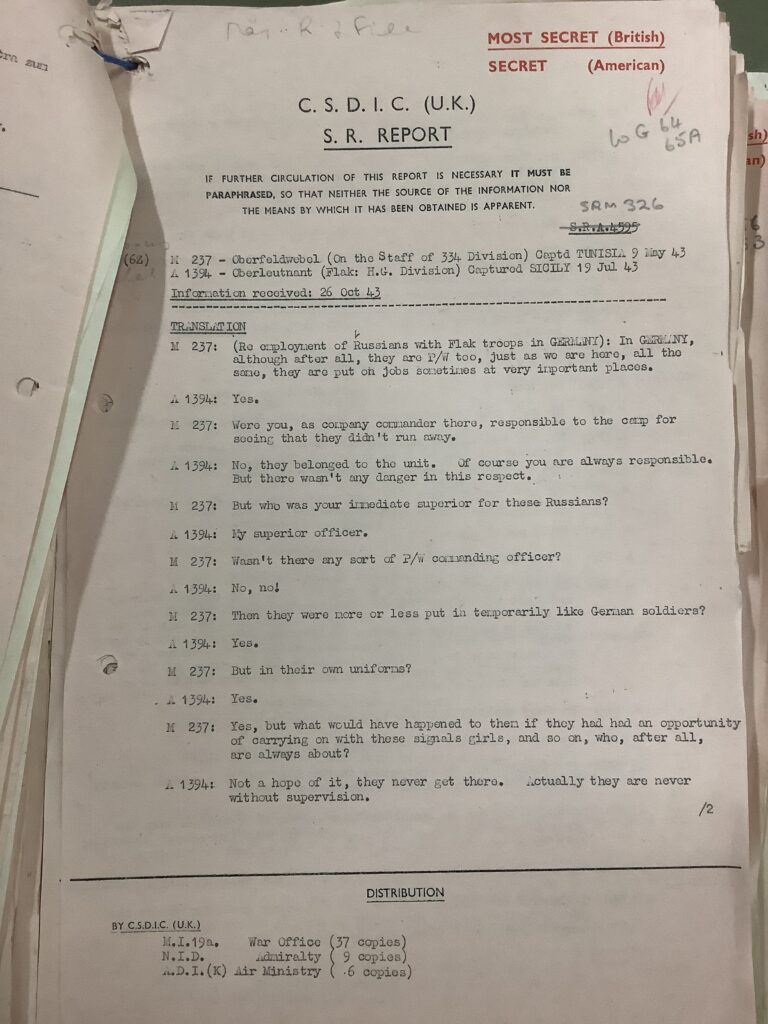

The conversations were then translated and typed into German and English by the women. The resulting text was known as a transcript

“We sat at tables fitted with record-cutting equipment – this was before electronic tapes were invented. We had a kind of old-fashioned telephone switchboard facing us, where we put plugs into numbered sockets in order to listen to the POWs through our headphones. Each operator usually had to monitor two or three cells. As soon as we heard something which we thought might be valuable, we started recording,” Fritz Lustig